Traditional men’s Edwardian dress shirts (1900s-1910s) came in three forms: the soft pullover style, the stiff bosom front, and the newer button down coat style. Each style had an appropriate suit or semi- dressy outfit to wear it with. Shirt collar types were usually detachable linen in tall stiff shapes until the post war years. Though collars were white, Men’s 1900s dress shirts were made in vibrant stripes and small patterns. No boring shirts allowed!

Men’s dress shirts, those made for wearing with suits, differed from men’s casual shirts and work shirts.

1903 red and white striped shirt for a summer semi-dressy outfit

Men’s Edwardian Shirt Styles

Men’s Edwardian soft dress shirts, called Negligee shirts, were made of light cotton madras, percale, or cambric batiste in spring and summer. The pattern, usually stripes or light plaid, was woven into the fabric. Cheap shirts may have had a printed pattern. In fall and winter, heavier weight cotton dress shirts were sold.

- 1916 Big and Tall Size Percale Cotton Negligee Shirt

- 1917 Silk Green Negligee Shirt

The 1900s and 1910s Negligee shirt came in the pullover style, with a long button plaquette ending either slightly below the waistline (which was high rise) or in the newest coat-style, which buttoned all the way down the shirt. A buttonless plaquette began halfway down, overlapping on the left side.

- 1905 Coat-Style Negligee Shirt in a Small Pattern

- 1906 Coat-Style Negligee Shirt in a Windowpane Pattern

Stiff front bosom shirts (celluloid) with a starched detachable white collar were what every traditional businessman wore. The shirt pulled on overhead, with three white pearl buttons fastening from collar to sternum. The size of the bosom was around 13-1/2 by 8 inches to 16 by 9-1/2 inches, but could be up to 17 by 19 inches. The bosom needed to cover the chest enough so that no soft part appeared under the vest. This helped keep men’s appearance neat and strong.

- 1910 Bosom Front Shirts in Starched (Laundered) or Unstarched (Soft)

- 1918 Bosom Front Shirts and Detachable Collars

Most bosom front shirts were white, but colors and patterns were also available in both starched, called laundered, or un-laundered options. Plain (smooth) as well as narrow and wide pleats were found on bosoms.

1915 Mushroom Pleated Soft Shirts in Bosom Style

1914 Smooth Bosom-Front Striped Shirt

The pleated-front soft shirt was yet another option for Edwardian men’s dress shirts. Inch-wide pleats were placed vertically down the shirt, starting at the collar and moving out halfway to the shoulder. They were popular in summer, where the pleating allowed for extra circulation.

- 1908 Pleated-Front Soft Shirt

- 1913 Pleated Shirts

Detachable bosoms, called dickies, were also sold as false fronts. They could be worn over another white or matching colored shirt with a detachable collar. They were ideal for men who wore tuxedos as uniforms (waiters, butlers, entertainers), especially when made of rubber. The laundry savings made them economical. However, they became a source of comic fodder when they suddenly rolled up and smacked the entertainer in the face!

- 1902 Pleated Dickie Fronts

- 1901 Striped Dickie Fronts

Shirt pockets were optional. About 90% of men’s dress shirts did not have chest pockets. Pockets were seen as being for the working classes. Since men had suit vests and jackets to carry small items, a shirt pocket was unnecessary. However, after 1910, a few soft shirts took inspiration from military men’s shirts and placed one or two pockets on the chest. These were worn only in summer, without a vest. The pockets had a square or envelope flap with a button.

1914 Soft Shirts with One or Two Pockets

Shirt Colors and Patterns

1900s and 1910s Edwardian era soft shirts came in more colors, patterns, and fabrics than bosom shirts. Chambray, linen, percale, Oxford, flannel and various cottons were common fabrics year-round. A twilled sateen was used in summer and was the lightest and coolest option besides linen.

- 1915 Soft Shirts, Summer Outfits

- 1914 Dress Shirts

- 1918 Solid and Stripe Shirts

- 1918 Stripe Shirts

Shirt colors and patterns were very bright. Blue and white vertical stripes, red and white stripes, lavender and white stripes, and burgundy and white were the most popular. The width of the stripes could be very thin or slightly wider, but never very wide or horizontal. Some stripes had patterns within them. Tiny polka dots and other small patterns spaced out all over the shirt were trendy as well.

Solid colors with subtle patterns were increasing in the late 1910s. Sage green, yellow, blue, and peach were trendy. Solid color shirts looked too much like work shirts, which is why most men, keeping up with their class status, chose stripes or patterns instead.

1901 Dot Silk Flannel Shirts

The all silk shirt became very popular in the post-war boom after 1918. Men who had wealth could afford the $20 price tag ($350 USA dollars in 2020). Cheaper washable tub silks cost significantly less, around $50-100.

- 1917 Silk Crepe de Chine in Yellow and Green Stripes

- 1917 Tub Silk (Washable) In Yellow and Purple Stripes

- 1917 Tub Silk (Washable) Shirt in Blue Stripes

Shirts were sold in neck sizes, most between 14-1/2 and 17 inches around. They were not sold by body size, except for a few made for “portly men.” Since most dress shirt-wearing men had clothes custom made by a tailor, this wasn’t an issue. For lower middle classes who ordered generic size shirts, the sleeves may have been too long and the body too wide.

There was no such thing as a slim fit shirt. Men’s shirts were full cut and quite long – 36 inches from shoulder to hem. The extra length was tucked into trousers, which themselves were high waisted and full-fitting around the hip/seat/crotch.

- 1901 Striped Shirt Color Combinations (Pink!)

- 1901 Striped Shirt Color Combinations

Shirt Collars

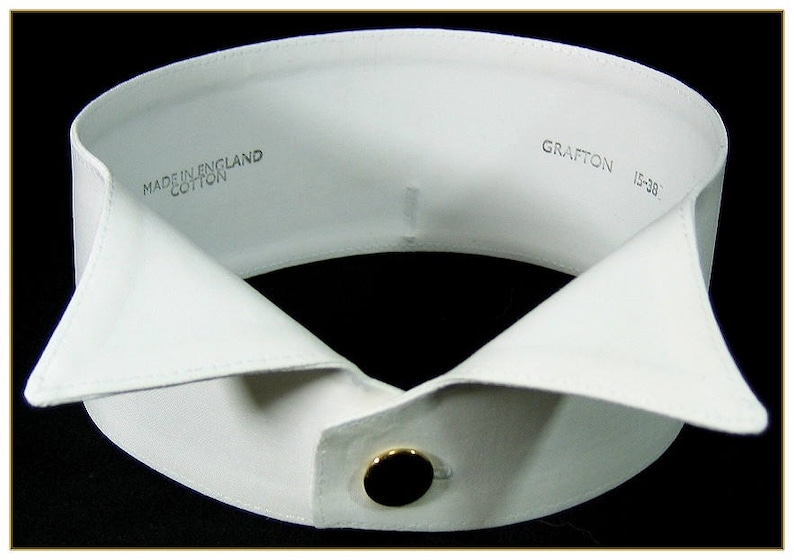

The typical Edwardian men’s business suit shirt had a narrow banded collar in which a tall detachable shirt collar made of stiff celluloid, linen, or rubber was attached in the front and back of the neck with a shirt stud. Detachable white collars allowed men to clean or discard dirty collars more often, extending the life of the shirt by a few years.

Many working class men who could not afford to buy many detachable collars, would wear a shirt without a collar to work or in a casual setting, saving a white collar for Church and special occasions.

1900, Harvey Firestone (1868-1938) standing with Henry Ford (1863-1947) wearing striped shirts, white collars and bow ties

There were attached collar soft shirts in the 1900s that some men who could afford frequent replacement could purchase. A man could also buy a shirt with matching detachable collar instead of white, although this was less common and considered too informal for a middle- and upper-class man.

Men returning from WWI preferred the military-style soft shirt with attached unstarched collars in matching shirt body colors. They were still slow to catch on, and the white detachable shirt collar wouldn’t fully disappear until the late 1920s.

1918 matching shirt and collar (and tie!)

In 1919, there was very a brief trend to wear a patterned shirt collar with a white or subtle stripe shirt. Some of the collar patterns were very bold, such as black and white checks.

Collar Styles

There were well over 400 different styles of shirt collars worn at the turn of the century. Every designer, tailor shop, traveling salesman, and mail order catalog had their own names for the collars they sold. This is why it is incredibly difficult to “name a style of Edwardian collar” today.

1918 Detachable Collars with Unique Style Names

The Poke collar is one name that describes many men’s early 1900s dress shirt collars. It stood high around 2-3/4 inches in front and 2-3/8 inches at the back. Shorter collars at around 2-3/8 inches at the front and 1″ to 7/8″ in the back were also common. The front edges could be slightly rounded for comfort.

A similar round collar was the Clerical collar for men of the cloth. It was fastened at the back only with a collar button, and in the front with a tabbed shirt button.

- Poke Collar with Necktie

- 1901 Poke Collar “Manhattan”

- 1907 “Straight Band” Poke Collar with Overlap Edge

- 1907 Clerical Collar

Wing collars were the most formal, usually worn with white tie eveningwear or dressy morning suits. They had points that folded down and stuck straight out past the necktie. Some less formal styles featured rounded edge wing tips.

- 1907 Classic Wingtip Collar

- 1913 Rounded Wing Collar

Stand collars, like poke collars, were the tallest collars and the most iconic of the decade. They featured a round collar that folded down over itself. They were uncomfortable due to the stiff starching required to keep them neat. In the later years, men could wear softer stand collars held together with a collar pin.

- 1903 Stand Collar

- 1911 Stand Collar

- Roger Calbreath Wears a Stand Collar with Collar Pin

- 1916 Men’s Stand Collar With a Tie Over the Pin

The Fold-down collar gained popularity after 1906. Its fame was made by the “Arrow Collar” man, illustrated by Joseph Leyendecker. He was strong, sexy, calm, and masculine. Women found the ads to be a great motivator in purchasing collars for their spouses. Arrow shirt ads from 1906 to the early 1920 were responsible for turning the company into a 32 million dollar business!

1916 Arrow Collars, Stand Collars

Fold-down collars could have rounded edges and small or large points, with a large or narrow V opening. The width of the opening accommodated certain ties and bow ties. Wide openings could handle a broad necktie, while a very narrow opening needed skinny ties worn under the collar.

- 1907 Open Fold-Down Collar

- 1918 Striped Fold-Down Collar

- 1909 Fold-Down Point Collar

- 1909 Ill-Named “Titanic” Large Point Fold-Down Collar

As the decade moved into the 1910s, especially during WWI and after, collar sizes decreased to 2-1/2 inches in the front and 1-7/8 inches in the back. The collar points were closer together, and two buttons and a loop held them in place.

- 1914 Pointed Collar

- 1919 Soft Collar with a Loop and Button to Hold it in Place

The Club Collar was one variation of the stand or fold down collar that had cutaway rounded edges. The edges could meet in the front or be open and spread by the end of the decade.

- 1908 Tall Club Collar

- 1915 Cutaway Club Collar

1900s Shirt Cuffs and Cuff Links

Dress shirts cuffs were made in matching fabric to the shirt body, while the collars were white. Cuffs were offered in attached or detachable options. There was a fold back French cuff found on most men’s dress shirts, but barrel cuffs were popular in the early 1900s. All shirt cuffs were secured with gold cuff links.

- 1903 Shirt Cuff Styles

- 1917 Men’s Shirt with Attached Cuffs Secured by Cuff Links

- 1908 Gold Plated Round, Oval, or Unusual Shaped Cuff Links

- 1902 Cuff Links: Pearl Button, Dumbbell, Plaid, Opal Pipe Stem Stud, Celluloid Collar Buttons

Men’s shirts were always long sleeved. In summer, rolling long sleeves up over the elbow was the only relief.

1918 Casual Golfing in Striped Dress Shirts

Read More

- 1910s Edwardian Men’s Working Class Clothing

- 1900s Men’s Suits History

- What did Men Wear in the Edwardian Era?

- Edwardian Men’s Formalwear

- History of Men’s Gloves in the 20th Century

Buying Edwardian Men’s Shirts

While there are some reproduction Victorian shirts and later 1930s + shirts, the Edwardian era is largely ignored. You can find a few detachable collars and collarless shirts from USA and UK sources, or buy modern attached collar shirts in similar stripe patterns.

When choosing the latter, look for classic fit shirts, not slim or trim fit. Choose white collars in the style you prefer, although options will be limited to the Club Collars or point collar. Most important is to choose a vibrant bold stripe pattern, not white, unless you need a bosom shirt for formalwear.

Here are some modern shirts, reproduction Edwardian shirts and detachable collars I have found online:

Debbie Sessions has been teaching fashion history and helping people dress for vintage themed events since 2009. She has turned a hobby into VintageDancer.com with hundreds of well researched articles and hand picked links to vintage inspired clothing online. She aims to make dressing accurately (or not) an affordable option for all. Oh, and she dances too.