1895 ladies coats

To stay warm in bitterly cold Victorian winters, women would wear a variety of capes, cloaks, coats, and jackets from the early 1840s to the late 1910s Edwardian era and WWI. Long coats covered the entire dress, but were usually capes with or without big bell sleeves. Small fur trimmed caplets were worn during sportier activities like ice skating. Victorian jackets and coats, similar to what we see today, emerged in the late Victorian era. They were hip length with lapels or a big collar just like the men’s version. During WWI, the two-piece suit with skirt and jacket took inspiration from military uniforms and became regular street clothing for active, forward thinking women. The driving coat was also common at the turn of the century and around the sailing of the Titanic.

Shop all of these Victorian jackets and coat styles inspired by the Romantic Victorian and Edwardian aesthetic, or make your own with a historically accurate sewing pattern.

Read on or click here to jump to a history of Victorian outerwear.

Victorian Coats & Jackets

Victorian Outerwear History

Cloaks, capes, mantles, coats, jackets

The out-the-door garments of the Victorian woman have so much variety that for identification and dating, it is perhaps easiest to divide them first according to the different main forms. First of all there were the cloaks — the true cloaks, sleeveless, all-enveloping, falling full from the shoulder at full-length or three-quarter-length. Their shorter versions were the capes. Then there were the full-length coats, cut with sleeves and fitting the figure or the shape of the dress. Their shorter versions were the last form — jackets.

Between these were garments — full-length, three-quarter-length, half-length or less — which lie somewhere between the coat or jacket and the cloak or cape, or between these and the shawl. For all these, the general term mantle will be used. This tidy arrangement means to a certain extent the ignoring of contemporary fashionable nomenclature, which at one date refers to almost any outer garment, whether with sleeves or not, as a cloak, and at another refers to coats and cloaks alike as mantles.

1858 pelisse wrap

At different periods, there were different dominant forms. At the beginning of the reign, the full-length fitted coat, which had been called a pelisse, had passed out of fashion, but the cloak was worn. The short cape was also worn, but during the 1840s, half- length and three-quarter length mantles of different shapes became increasingly fashionable. Jackets were worn only a little in the 1840s and appeared more often in the 1850s, but were one of the main styles of the 1860s. They were fashionable then in many varieties: very short, half-length or three-quarter-length in loose forms or just three-quarter-length in fitted forms. At the same time, short circular capes and three-quarter-length cloaks were also fashionable. The short jacket, in new shaping with basques to fit the new lines of the dress, continued to be worn during the 1870s, and in the late 1870s extended in sheath form to a fitted three-quarter-length coat. Meanwhile cloaks and capes were less worn. During the 1880s, mantles in great variety were the general form, and coats and cloaks less characteristic. These returned again in the early 1890s. Short capes were also particularly fashionable in this decade.

Victorian Cloaks

1863 cloak

A cloak was often worn for comfortable out-of-door wear in cold weather in the late 1830s and early 1840s. The cloak of this date was a voluminous garment, usually falling from a yoke and not easy to distinguish from a cloak of the early 1830s. Many were made of silk, lined with silk, and interlined with an extra layer of wool (or padded) for warmth. To give yet more warmth, an additional cape or deep collar sometimes fell over the upper half. Other cloaks were made of woolen cloth of various weights, usually with a silk lining. Only the very utilitarian ones had wool also for a lining. The seams were usually piped and there were slits for the arms. The circumference at the hem was usually between three and four and a half yards.

Some of the dresses of the late 1830s and early 1840s were made with matching capes which reached to about the level of the elbow. There were also longer capes falling below the waistline of the dress. Most of them were seamed over the shoulder and down the arm, A-line, and cut, which made the characteristic falling curve of the 1840s. Some were also shaped by darts at the neck. Silk was the usual material for them apart from those which matched their own dress. Some were lined, but a large proportion were left without lining.

1865 Worth day dress with cloak

The full-length cloak grew rarer during the 1840s. Three- quarter-length cloaks were worn, but cloak and cape forms were less usual than varied forms of mantle. The simplest of these mantles were very close either to the cape or the triangular shawl and had very little shaping. They were round or pointed at the back, slightly shaped for the arms and with darts or horizontal pleating at the neck. In the scarf mantle, this cape or shawl over the shoulders was extended to form scarf ends in front. Mantles of this shape, particularly in embroidered muslin, had been worn in the early 1830s. With several variations of shape and with increasing emphasis on the mantle and less on the scarf ends, they were one of the main forms of the 1840s. Other mantles had cape-like sleeves, falling over a three-quarter-length cloak. They were made in silk, particularly in the changeable silk of this time, velvet, or muslin. Many of the silk mantles were unlined, but the velvet ones were usually lined with silk. They were trimmed with falls of lace, with ruching, with pinked and scalloped edge, with fringes and bands of applied velvet or silk braids. The applied curving lines of fringe often suggested a V series of capes. Fringed trimmings became increasingly popular by 1850. Apart from the use of black lace with colored silks, the trimmings usually toned with the material of the mantle.

These mantles bear a variety of names—visite, paletot, pardessus. One may work out by careful comparison of fashion engravings and fashion notes what appears to be the difference between them, only to find that, by the next year or even the next month, what was called a visite now appears identical with a pardessus, and a paletot is now something quite different.

Coats and Jackets

1850 cloaks

Coats and jackets were not worn a great deal in the 1840s. They were mostly three-quarter-length or a little shorter, usually with a fitted bodice and sleeves and a full skirt over the hips. For eveningwear, there was also a loose jacket with wide sleeves, which at this time was usually called a sortie de bal. The same term, when used twenty years later, meant a circular cape worn with evening dress.

Jackets grew more fashionable during the 1850s when the dress also often had a jacket bodice. As the sleeves of dresses opened out into the wide pagoda form that was fashionable in the mid-1850s, the shaping of the jacket bodice approached that of a mantle with a fitted bodice and full skirt.

In the second half of the 1850s, A new type of jacket appeared. Falling loose and straight from the shoulder with wide sleeves, it was plain in line, short or three-quarter length, and had little trimming. By 1860 jackets of this kind, and fitted jackets with closed or open sleeves, were very much worn.

Coats, either long, ending a few inches above the hem of the dress, or three-quarter-length, were also worn in the 1860s in both forms, hanging loose from the shoulders, or with a fitted bodice and a skirt spreading over the full skirt of the dress. The sleeves were either loosely fitting sleeves with cuffs, or wide-open sleeves. Some of the coats were belted at the waist, particularly in the second half of the 1860s. The jackets and coats, particularly some of the shorter jackets, often had a double-breasted form, with buttons and pockets that were more conspicuous than they had been for a long time on women’s dress.

“Why do ladies affect gentlemanly attire, I wonder . . . why do they not leave to the sterner sex the paletots and pocketed jackets with large buttons, which are their special attributes. From Garibaldi they took his shirt, from the fierce red-stockinged Zouave his jacket” (Queen, 1862). “

1864 Zouave Jacket

The Zouave jacket was a particularly characteristic garment worn between 1859 and 1865. It was a very short jacket with an open front cut away at the waist. It was often made in a scarlet woolen fabric and trimmed with gold braid, black braid or black and white stitching. It was usually worn over a white habit shirt, or a white Garibaldi bodice. Many of these short loose jackets were made in light woolen fabrics such as cashmere, and were used for seaside or very in-formal wear out of doors, and sometimes even as indoor jackets.

1859 Zouave Jacket

1857 jacket

Heavier woolen materials were used for winter coats and jackets during the 1860s, far more than they had been earlier in the period.

The three-quarter-length cloak and the short cape were also worn in the late 1850s and during the 1860s, both for day and evening wear. They were now usually circular in form, some with a seam down the center back. They were made in many different fabrics, and were sometimes made to match a dress. For evening wear, light soft woolen materials were particularly fashionable. There were many evening cloaks and capes of white cashmere, some trimmed with gold braid or black lace, some lined and trimmed with blue silk. Others were made in the more transparent woollen fabrics and left unlined. Some of these fabrics were woven with silk in striped patterns. Many of the evening cloaks had tasseled hoods.

Although the jackets, cloaks, and the more circular cloaks and capes were all worn, the mantle never completely disappeared. The cloak forms with open sleeves followed the general style of the earlier mantles, but were now mostly large and shawl-like. Even more shawl-like was the burnous, a fashionable evening mantle of the early 1860s. The name had come into the fashionable vocabulary as early as 1837, when a writer in the World of Fashion referred to the “Bernous, imported from Arabia, now naturalized among us.” The burnous mantles first bearing this name do not not suggest anything very Arabian, but by the late 1850s, the burnous was usually made of a folded scarf of cashmere or other woolen fabric sewn together at the back and tasselled to fall like a hood, giving it a stronger suggestion of its exotic origin.

The trimming of the loose jackets and capes was often in borders of applied braids or stitching in arabesque patterns, particularly in black on bright or light colors and white on black. Gold on white was much used for evening wraps. Trimming falling from the top of the cloak at the back was characteristic of the 1860s. Many cloaks and capes from the late 1850s and 1860s had borders of quilted silk. In the late 1860s, beaded braid and fringe was popular everywhere as a trimming and appeared on both dresses and outer garments.

In the early 1870s, the cloak and cape forms continued for evening wear, and the short cape for day wear. The material used for them changed, the lighter woolen fabrics gradually disappearing and poplin and corded silks joining the still popular cashmere. The pleated frills, which were a characteristic trimming of the 1870s, appeared on them and are a mark of this date.

1857 Basque Jacket

The loose short jacket was still worn in the early 1870s, but now often had fringed trimming and was open below the waist at the center back. Other short jackets had a pleat down the center back, usually referred to as a Watteau pleat. This appeared in both jackets and mantles. The form of jacket or coat which was particularly characteristic of the early 1870s was one with a loose straight front and a closely-fitting back, ending in a deep basque. In the shorter jackets, the basque was usually open at the center back and sometimes also at the sides, forming a short, tabbed skirt. In the longer coats, the polonaise form of the dress was repeated, a fitted bodice with the skirt puffed at the back over the bustle and open in front. These were usually three-quarter- length. Some of them had the waist defined by a band. They had different forms of sleeve; a fitting, but not tight, sleeve with a cuff, and an open pagoda sleeve were the two main forms.

1874 fitted and pagoda sleeve jackets

After 1875, coats shared the changing lines of the dresses and lost their basques and fullness. The fashionable coat-form of the late 1870s was a closely-fitting coat, three-quarter-length or longer, showing a long, continuous line. This line was emphasized by the plainness of many of the coats, which were shaped closely to the figure and buttoned down the front. Some were double-breasted, particularly those made in heavier cloth for traveling wear. These traveling coats, which often had added capes, were long, ending just above the hem of the dress, and were, from this time, often known as ulsters. Sleeves were usually fitting and often cuffed, but some were influenced by the dolman forms of sleeve which were general in the mantles of the 1870s.

1891 fitted coats

Victorian Mantles

1857 Mantle

The mantles of the early 1870s, like the jackets, often had a pleat at the back. Some with this loose back were slightly fitted in the front; others had a fitted back and loose front. They differed from the coats and jackets in that they had sleeves falling as capes from the shoulder, sometimes with longer, hanging ends. In the first half of the decade, those with fitted backs had the basque form of the coats. In the second half, some mantles had the same fitted lines as the coat, but with sleeves cut as capes over the shoulder or as square-ended openings at elbow-length; others had long, hanging ends in front with a cape at the back, an 1870s version of the mantle with scarf-ends.

The mantles generally had more trimming than the coats and jackets. Fringes were the usual trimming throughout the 1870s and, by the end of the decade, beadwork appeared everywhere: “every article for outdoor wear is beaded” (Ladies’ Treasury, 1880). Fur was used in the traditional way as a trimming for outdoor garments and jackets but in the late 1870s the fashion for coats and jackets entirely of fur was beginning: “The rage of the season … is for a sealskin jacket trimmed with otter or beaver” (Queen, 1872).

1873 Visiting coat and dress trimmed in fur

During the 1880s, the mantle was the usual form. The long, slim line of the late 1870s continued for the first years of the decade and the longer mantles generally increased their length, so that often only the hem of the dress was visible beneath. The use of the dolman types of sleeve was general in all these full- length forms, turning the coat into a full-length mantle, fitted in all but the sleeves. From 1883, the slimness of the line broke to take the increasing fullness in the skirt of the dress. The fullness of the evening mantles was given either by pleating, falling from the waist at the center back, or by the width of the cape-like side sections, gored to a narrow back width. There was sometimes a combination of both these devices in full- or three-quarter-length mantles.

1883 mantels or wraps

Short mantles were also worn, in great variety, in the 1880s. Some had fitted backs, ending at the bustle, or were a little longer, opening to go over it. They were usually trimmed at this point with a bow of ribbon. The back and front sections were usually narrow and the cape shaping for the arms, full. This form with the wide cape from the shoulder continued to be worn on both long and short mantles, but the short sleeve starting from the elbow was perhaps the more general form for the 1880s. Sleeve shaping which ended at the elbow and revealed the lower half of the arm also appeared in the lighter mantles of this time. From 1885, the sling sleeve, formed by the front section of the mantle being turned up inside to form a sling, was a distinctive fashion. Many of the shorter mantles had their narrow fronts extending into scarf ends.

1886 long mantels and winter fur coat

Short jackets, usually in cloth, were worn as a plainer fashion. Shorter than the fitted jackets of the 1870s, they were made with closely fitting bodice, and basque-shaped with pleating at the back to lie closely over the hips.

1889 short close fitting jackets

There were short capes of two kinds: one was a decorative addition to the costume, light in fabric, but heavily decorated, usually with beads; the other was a short cloth cape, often a double or triple cape, which appeared in the second half of the decade as a driving cape.

A large proportion of the mantles and capes of the 1880s were black. The fabrics used for them were velvet and corded silk, and also the lighter fabrics, net or lace, weighted with bead embroidery. Mantles in bright, rich colors were usually in plush, one of the most characteristic fabrics of the 1880s. The heavier figured silks were also fashionable and appeared in the mantles. Figured materials other than silk were also used, and there are many examples of a woven shawl of earlier fashion being cut up to make a mantle of the 1880s. The weight of the heavier winter mantles was often increased by a quilted lining. The mantles bore a great deal of trimming, chenille fringe, silk fringe, edgings of fur and feathers, lace, braid and beaded braid and embroidery.

1890 short jackets, high necks

From 1884, jackets and mantles of daywear often had a high fitted band at the neck, like the dresses. At the end of the decade, both the true sleeve of the jackets and the sleeve-shaping of the mantles—which usually included a seam over the shoulder from front to back—rose above the shoulder seam. This high shoulder is a mark of the years 1889 to 1892 and was followed by the swelling out of the sleeve into the full leg-of-mutton sleeve of the mid-1890s worn from 1893 to 1897. Another distinctive mark of this decade in its outer garments was a high collar, often as high as the ears, standing out from the neck, sometimes lined with feathers or ruched silk.

The mantle forms of the 1880s continued in wear until about 1892; but they were already passing out of fashion by 1890, except in one or two forms which occasionally appeared as variants of the cape during the 1890s.

1891 capelet short coats

Victorian Capes

1894 capes

The short, full circular cape was perhaps more worn than any other outer garment in the 1890s, although it became a dominant fashion only with the rise of the full sleeve in 1893. It appeared on all occasions and may be found in many different fabrics. It was worn as an evening wrap, in silks, and trimmed with feathers, fur and beading. For day wear it appeared in the smooth-surfaced face- cloth that had now become popular as a “ladies’ cloth,” plain or with trimmings of braid or patterned applique of cloth. For travel and sporting wear there were capes of tweed, often lined with brightly colored plaids and sometimes with an additional cape and hood. The evening and dress capes usually had the full circular collar, which is like an inverted miniature of the cape itself. The tweed capes usually had a smaller, square-ended collar.

1890 capelets

1895 Mutton Sleeve Coat

Full-length cloaks were also worn throughout the 1890s. At first, they fell, with high shoulder line, rather slim and straight, often from a square yoke, but by 1893 they showed a greater fullness, to take the full sleeves beneath. The fullness was given often by a double pleat falling from the neck or yoke at the center back. This pleating is found on cloaks, coats and jackets to the end of the century. It is a reappearance of the shaping that was occasionally used in the 1870s. Once again it was often called a Watteau pleat. It derived from a construction used over a long period of the eighteenth century, but never then known by this name. By the end of the century, another, less enveloping form of cloak appeared, with the fronts cut in a curving line to reveal part of the gown beneath.

A full-length coat was also worn for both day and evening wear during the 1890s. The early 1890s coat was usually a plain fitted form with a high sleeve and a high shoulder line. After 1893, the fitted form continued, with the sleeve widened to take the full sleeves of the dress; but a yoked form, with the fullness falling from a central pleat, like the cloaks, was more general. After 1897, the sleeve was once more close to the arm. By the end of the century, it was becoming wider at the opening. At the same time, the fronts of the curved coats open to a wider line at the hem.

1894 full length coats

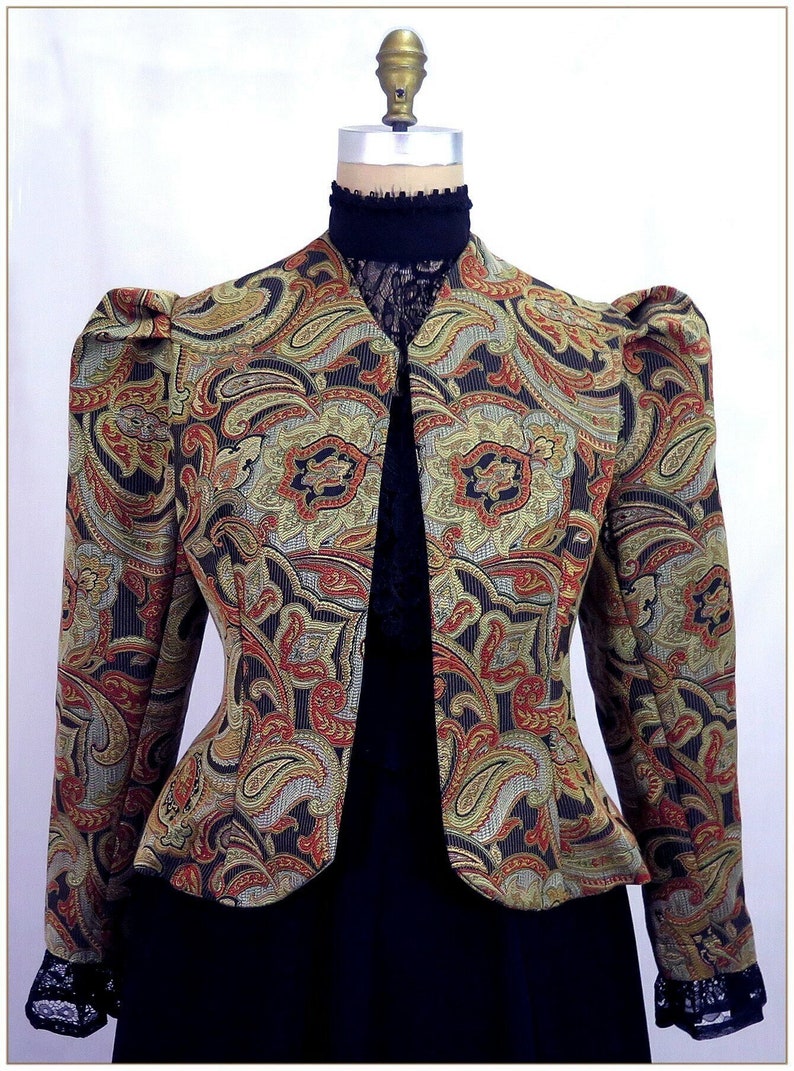

The fitted form was much worn in three-quarter-length coats and also in the jackets which ended at the waist or in a short basque below it. The jacket was a popular fashion for day-time wear. It was worn with a skirt or dress, either matching or contrasting in color and material. It appeared in both single and double-breasted forms. Loose jackets with yokes were also worn in the second half of the decade. Like the capes, the short jackets had great range of wear and were made in many materials from tweed to velvet, with elaborate trimmings of lace and embroidery or braidings. Very short jackets, not unlike the “Zouave” jackets of the 1860s—a name sometimes used again, although they were now usually called boleros—appeared in the late 1890s. Their curving lines repeated the line then appearing at the lower edge of most of the outer garments of this time.

1897 Cape Coats

The cape form was so dominant a fashion that short capes appeared on coats and three-quarter-length jackets, and even the trimming added to the necks of many of the more elaborate cloaks, capes, coats and jackets—in ruches and pleated frills of chiffon or lace—showed a cape-like form. On the jackets, the reverse were often large and emphasized by decoration or the use of a contrasting material. They were often elaborately braided and were sometimes worn with a matching vest. Evening cloaks, coats and capes showed an increasing richness and elaboration in fabric and trimming. In the second half of the decade, the linings also became very elaborate, and this concentration of ornament on a lining is seen again in the parasols of these last years of the century.