The Victorian 1880s fashion decade marked the end of the bustle era. To understand fashion during this decade, you must begin in the mid-1870s, where the bustle was still large but the bodice was forming a new style that would last the next 15 years. Upper-class women embraced these new fashions, while the poor and working classes lagged behind.

1880s fashion

The 1880s is one of my favorite Victorian time periods. With this article, I hope to teach you a bit about women’s 1875-1880s women’s fashion history, followed by outfit ideas you can make (with little to no sewing) or purchase online. If you need help with your costume, please feel free to contact me anytime.

Jump to 1880s clothing for sale.

1875-1880s Dresses

From Victorian Costume and Costume Accessories by Anne Buck, published 1961, copyright expired

The dress of 1875 shows a complete change in line and character from the dress of the years before 1874. The governing factor of this change was the cuirass bodice which appeared in 1874.

1875 fashions

This was a bodice which had lengthened, descending in a point back and front and lying closely over the hips instead of ending in the full basques of the early 1870s. This long-waisted bodice smoothed away all fullness of the dress over the hips and appeared to push the fullness of the skirt down from the upper half of the back to the lower half.

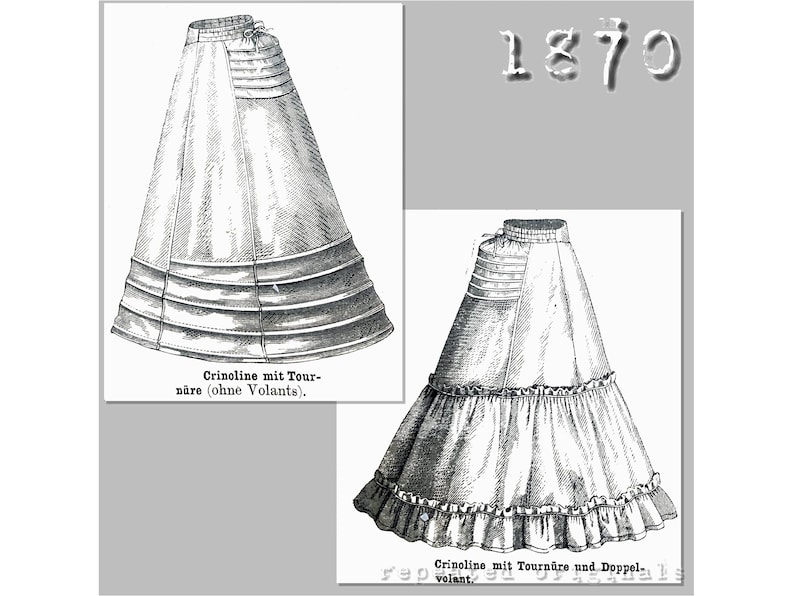

The bustle, which had given shape to the skirt of the early 1870s, grew smaller and was brought lower down the skirt so that “the tournure is now arranged low down, nearly to the heels” (Ladies’ Treasury, 1876). The back fullness flowed out in a train.

- 1874, large and high bustle

- 1875 new lower and smaller bustles

For once a fashionable term is exactly descriptive of its subject. The cuirass quality of the bodice was emphasized between 1875 and 1877 in a version which was sleeveless, or appeared to be sleeveless by having the sleeves of a different material.

As well as the cuirass shaping, there was, between 1879 and 1883, a long coat-like bodice form which fitted the figure closely, ending in a straight line below the hips. A loose-belted bodice which appeared in informal wear was an occasional, alternative to these dominant corset-like forms.

- 1875 contrast sleeves with a cuirass bodice

- 1876, Spain, a jacket like bodice

With this new long-waisted bodice, the skirt also was tightened over the hips, so that it fitted without fullness at the front and sides. It was tied back inside, beneath the back fullness, which drew it tightly over the figure in front. The skirt was narrower and set without fullness at the waist.

All remaining fullness was brought to the back to flow into a train: “that the bodice be as long-waisted and tight-fitting as possible, the skirt as scant and the train as full as may be” (Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, 1875).

The skirts of most dresses were now so long at the back that they had to be lifted up for walking. The sheath-like form of the front of the skirt was partly concealed by drapery which formed the main ornament of the dress. The usual form of this between 1875 and 1879 was a tunic or apron draped over the front of the skirt. Sometimes a wide sash was used in the same way.

- 1876 bustles pulled to the back with a wide ruffles train

- 1876 her large bustle reflects the earlier styles but the apron front is new

A critical contemporary comment gives more vividly than any more detailed description the aspect of this first phase of dress between 1875 and 1890:

“Sashes tied at the back exactly as a woman would tie on an apron to wash dishes . . . who has not seen a gardener at work with black tight-fitting jacket and white or grey sleeves. Behold the cuirass with sleeves of a different color. Next comes the tablier or apron and sash, exactly in form as those of a dish washer” (Ladies’ Treasury, 1875). *

The Dress Skirts

The cuirass bodice was worn with a separate skirt. The polonaise of the early 1870s, a bodice with a skirt attached, took the new sheath-like line and was worn as well as the separate bodice and skirt form.

Some of the polonaises of the late 1870s are almost as long as the dress itself and are then almost indistinguishable from a princess dress, a form which also appeared in dresses of 1878 to 1880, particularly in informal indoor styles, which were fore runners of the teagown.

1880s jersey over a skirt with draped front

These three forms of dress may all be found in dress between 1875 and 1890, but the construction of dresses at this time is confusing, and dresses will be found which have a princess form for the back, but a separate bodice in front ; or sometimes they may have a princess front and a bodice detached from the skirt at the back.

As in the early 1870s, the tunic drapery of the skirt could be attached to the bodice, making it a polonaise, or it could be attached to the skirt. An overskirt completely separate from the skirt, often found in dresses of the early 1870s, is rarely found in the later, more elaborately draped, forms.

1874 overskirts

The different phases within this period are marked by the changes in the fullness, construction and drapery of the skirt. Complete change came only in the late 1880s, when the skirt at last shed its looped and swathed tunics above and its supporting structures beneath.

The movement towards this change is, however, apparent throughout the 1880s. The dresses which are significant, which prepare the way for the newer, freer style, are the simpler dresses, the informal cottons and light woollens worn for seaside and country holidays, the tailor-made dresses of woollen cloth.

Plaid and stripe day dresses for the upper classes

“All dresses —be they of habit cloth, tweed, serge or any woollen material —are however made in a simple and in many cases almost severe style; perfect fit and excellence of workmanship alone being relied on to produce the—we must say it—mannish effect, which is unhappily the prevailing taste” (Queen, 1883).

1876 lower class ladies cotton dress. The style is a few years old and lacking trim or a large bustle. From The Paradise series

Many surviving dresses of the 1880s show this new emphasis in their plain, untrimmed lines and excellent tailoring, and the dress of the second half of the 1880s shows its penetration into all forms of dress, which finally brought the new style of the 1890s.

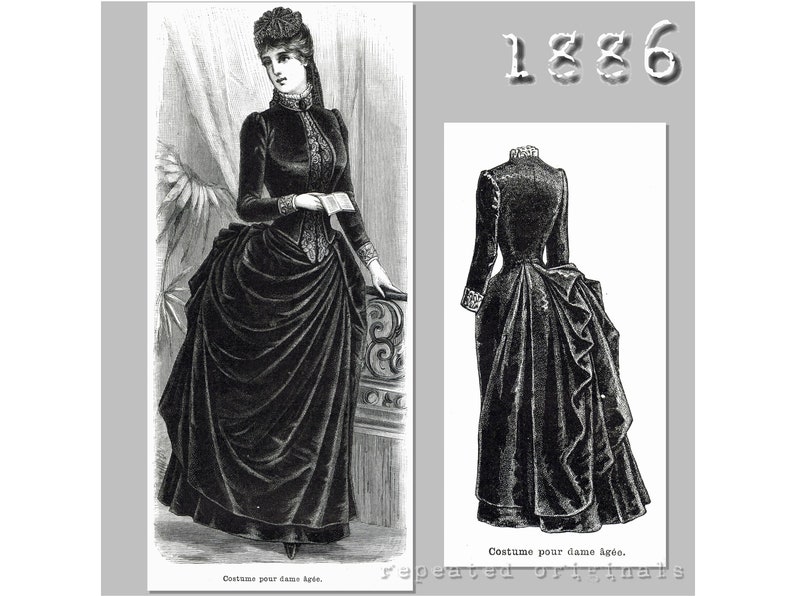

“All elaborate frillings and puffings are fast disappearing in favour of straight, falling lines. The under-skirt is now often completely hidden except at some point where the square apron or tunic is raised on one side” (Ladies’ World, 1886).

1875 dresses

For the more fashionable and formal dresses in the first phase, from 1875 to 1883, “The great aim is to make the figure as flat and sheath-like as possible and upon the block to wind as close as may be all kinds of draperies” (Ladies’ Treasury, 1875).

Between 1875 and 1879, no fullness appeared in the skirt at the sides and over the hips. In 1876 it was “at most three yards round the hem” and much of this was in the train which flowed out from the confined fullness at the back.

It grew narrower and more sheath like until 1879. The trained form appeared in all fashionable dresses during these years. “Dresses are worn trained, but they are easily looped up with hooks and loops” (Ladies’ Treasury, 1876).

1878 – very slim line, minimal bustle dresses

From 1878 short dresses without trains began to appear, first of all for walking dress; and by 1880 the train, except in evening dress, had almost disappeared. The loss of the train gave a new line to the skirt and its draperies.

Lacking the pull to the back, the skirt was no longer strained closely to the figure at the front, but fell as a straight, narrow tube, a tube concealed beneath flounces and frills and puffed and gathered bands, which were arranged in horizontal bands or in a series of deep short curves, above vertical pleating at the hem.

1881 plaid dress

Amongst the many draped tunic forms, one style became particularly fashionable for everyday dress at this time, and remained in fashion for two or three years.

This was the “handkerchief” dress, in which the tunic fell in points over a narrow kilted or pleated skirt. “At the seaside nearly all the dresses for morning wear are handkerchief ones which have been more popular than ever this summer. They are made in all materials, washing ones chiefly” (Sylvia’s Home Journal, 1880).

1882 handkerchief apron skirted walking dresses

The dresses were made in material which was made in squares for this purpose. Another style, which became a general form, was a tunic looped up in two puffs or panniers over the hips. This was a style which marked the beginning of the second phase of this period, the movement away from the sheath-like skirt. The panniers may be part of a polonaise or they may be attached to the skirt.

They brought to dress a widening of the hip line, a concentration of fullness at the hips, which once more needed the support of a bustle. Pannier draperies were a revival, with a difference, of the polonaise of the early 1870s. They were also a conscious revival once again, of a style of eighteenth-century dress, an influence which is recurrent in the fashionable dress of the 1880s.

“Very effective on the green grass are the Pompadour cottons over plain colored petticoats. They are simply made. The skirts are flounced and sometimes edged with lace, the tunic sometimes a Watteau, merely looped up at the sides and back, opening up at the front” (Queen, 1880)

1884, panier style draping around the hips

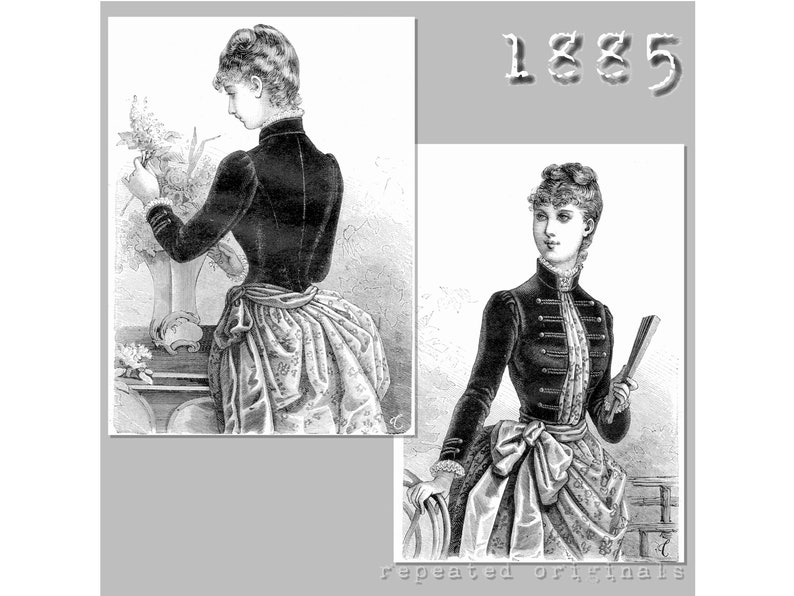

The complex construction of draperies over the skirt had, by 1885, already become less trimmed, though more voluminous. ie panniers of the early 1880s were sometimes constructed with a puff at the back but often ended at the back in “waterfall” draperies, that is, with the back breadth of the skirt pleated closely at the top into a narrow section at the back of the waist, the pleats being held together by tapes at the back of the dress.

Pleated trimmings which had persisted throughout the period from the early 1870s, now became pleated skirts or overskirts.

“Kilted or box-pleated skirts with vest bodice are the most usual, the long, pointed and very gracefully-draped shawl-shaped tunics being decidedly the favorite” (Sylvia’s Home Journal, 1885). This shawl shaped drapery resembled the drapery of the handkerchief dresses of the early 1880s, but was fuller and on a larger scale.

- 1882 promenade dress with kilted pleats

- 1882 house dresses with box pleated skirts

The apron-draped front appeared again on the new skirt of the mid-188os, as it had also on the skirts of the mid- 1870s, and on the skirts at their narrowest about 1880. In the late 1880s there was a fashion for asymmetrical drapery: “Skirts now never have two sides alike” (Lady’s World, 1887).

The shaping of the skirt was given by a bustle. It began to appear in 1880, increased in size to 1887 —when it began to diminish—and disappeared with the new shaping of the skirt in 1889.

“Our best dressed women . . . eschew drapery, even sashes, but accept the plain falling skirts, just as they are, with no dress improver and often with no steel ; though a short thin one, eleven Figure 9.—Bustles and Petticoats (Myra’s Journal, 1884)

1883 dresses with asymmetrical aprons

Unlike the bustle of the early 1870s, which spread across the width of the back in a wide shallow curve, the 1880s bustle was a narrower structure, which hung down the centre of the back, or was part of the construction of the dress itself, hooped steels often being inserted in the skirt lining to give the fashionable line. Bustles were also made of horsehair and of wire.

The construction of skirts throughout the period was complicated and various.

In 1875 the skirt was shaped in gores so that there was no fullness at the waist at front and sides ; the back, usually two widths, was set in a deep box pleat, a construction which continued until about 1880. These skirts were often unlined except at the hem, where a stiffened “demi-petticoat” was added to give the flow of the train.

A “balayeuse” or pleated frill of muslin, white or matching the dress, was also added to protect the hem. During this period of trained dresses, from 1876 to 1882, the train was often made detachable.

1876 trained skirt

An outside pocket was sometimes added low down the skirt at the back in dresses of 1876 to 1878. For the rest of the period, it would perhaps be true to say that generally there is no real skirt at all, but an application of drapery and trimming to a lining or foundation.

It was this foundation, usually stiff muslin, cotton satin, alpaca or silk, which gave the functional width of the skirt, the limit of distance which one leg made in front of the other.

Nearly all the skirts of the late 1870s have pairs of tapes inside across the back breadths for their tying back. These tapes continued to be used throughout the 1880s, to keep the fullness of the skirt in place over the bustler.

1880 plaid dress with an bustled overskirt

The skirts of this period are formed by their draperies, which show great variety, ingenuity, and elaboration. Certain types of trimming are, however, characteristic of the different phases. Narrow and closely pleated flounces are found as part of the ornament on the majority of dresses between 1875 and 1885.

Between 1875 and 1880 they were usually combined with flatly draped folds of material, falling, in curves.)

By 1880, silk fringe was less used, but chenille fringe was fashionable between 1880 and 1885. Lace reappeared, gathered in soft frills and flounces, and was used in large quantities on dress throughout the early 1880s. The flat folds of material were succeeded by flounces, gathered at top and bottom, forming puffed bands over the skirt. These were often combined with the pleated flounces.

- 1882 ruffles and flounces

- 1888 lace flounced underskirt

This type of trimming may be found from 1875, but it was chiefly used between 1879 and 1883.

After 1884, the skirt draperies became looser and freer. Instead of layers of narrow pleated flounces the whole skirt fell in pleats, and the tunic, still draped over it, fell in plain folds.

Lace still edged the draperies in some dresses, but the period of lavish trimming for day dresses was over by 1885. Loops and bows of ribbon may be found everywhere on dresses of the early 1880s.

The bodices of day dresses of all forms, whether cuirass bodice, polonaise or princess robe, were becoming high to the throat by 1875.; or, if they opened in a V-shape or revers, they were filled with a high-necked or higher V-shaped waistcoat or chemisette, of white muslin, with a high pleated or frilled collar. A high, close neckline would have a pleated white frill.

- 1875 Bow tie and high collar

- 1878 ruffled lace collar and front trim

By 1879 a double collar of pleated lace worn outside the dress, with one frill lying across the shoulders and the other a standing frill round the neck, became fashionable and was worn for the next few years—”throatlets of satin, edged on both sides with lace” (Queen, 1880).

From the 1880s a large proportion of day dresses had a standing collar of the material of the dress, which grew higher between 1885 and 1890. This was finished by a narrow white frilling sewn inside on plainer dresses.

Small capes and yoke-like collars of lace were worn in the early 1880s and also gathered frills of lace at the neck Jabots of lace falling down the center front of the bodice were fashionable in the mid1880s, and lace cravats tied with a bow in front.

1883 lace collars and fichus

Day bodices generally fastened at the front throughout the period,- but, in 1880, “The most stylish bodices are those fastened at the back, having long basques and sleeves with puffs at the shoulders, while the fronts have a V of very closely gathered silk let into them” (Queen, 1880).

This decorative shaping over the front of the dress was followed by the wearing of waistcoat fronts, which persisted for several years from 1883, when it was noted that: “A striking feature of the fashions of today is the introduction of the waistcoat into all costumes for morning and street wear” (Queen, 1883).

This waistcoat front appeared in bodices for most of the 1880s: “Waistcoats . . . their outline still meets us at every turn” (Lady’s World, 1887).

Sometimes the front was like a man’s waistcoat, but very often it was a plastron, either pleated vertically or gathered top and bottom, so that it made a puffed panel down the centre of the bodice, and it was either revealed by the bodice opening, or applied as a drapery over it.

The waistcoat or plastron was in a different material in the same colour as the bodice, in a different colour of the same material, or different in both color and fabric. Lace was also much used in this position in the mid-188os.

1882 polonaise dress with vested blouse under the V button up bodice

The bodice, whether it ended at the waist or extended into a polonaise or princess robe, was cut to fit the figure closely in narrow sections, elaborately boned. Bodices were almost always lined; the lining was often cotton satin, and some times it was striped or figured, but silk was used in some of the more expensive dresses.

The back of the bodice, which had usually been cut in four sections in 1875, was, by 1880, cut in six or eight narrow sections, usually with a bone at each seam, a bone at the side seam beneath the arm and two bones each side of the front opening where the front sections were shaped by darts. Boning was sometimes inserted at the front fastening.

Many of the separate bodices which ended at the waist have in the 1880s a narrow basque at the back, a continuation of the two central sections. The shoulder seams were placed far back on the shoulders.

1882 bodice back cut in four pieces

1880s Tea Gowns

The tight sheath-like form of both day and evening dress accounted in part for the appearance of a special form of dress in the late 1870s. This was the tea-gown. At first it was only a little more elaborate than the morning robes, but during the late 1870s it became less and less like a dressing-gown and more and more like a fashionable dress.

The basic difference was that the tea-gown had a loose, unboned bodice. Many of them were in the princess form; and a “Watteau” back, falling in a wide box pleat from the shoulder, often appeared in these gowns in the 1880s.

1883 Watteau back tea gown

The growing severity of the tailor-made dresses in the 1880s also gave the tea-gown a special place as the most elaborate garment of daytime wear, as well as the most relaxed and easy of any style of dress. Tea-gowns were much worn in the 1880s and have survived in some numbers.

They grew increasingly elaborate throughout the decade, as dress generally grew plainer ; “Easy, soft, flowing tea-gowns” could be worn for informal dinner dress, but “It is not considered that they are in good style if they in any way suggest a dressing-gown or wrapper” (Woman’s World, 1888).

Tea jackets worn over any skirt were an alternative of the late 1880s. These also were never so loose as a dressing jacket, but had greater ease than the usual dress bodice.

Learn more about the history of Tea Dresses. Shop Victorian-inspired dresses.

1889 tea gown, more like a house wrapper

1870s-1880s Ball Gowns, Evening Dresses

In evening dress, between 1877 and 1882, it was often cut to a very low point at the back and front, but curved high over the hips at the sides.

A neckline cut low and square in front, but high at the back, continued to be fashionable for evening dresses in the late 1870s; but this was less worn by the mid- 1880s and, in 1887, a writer in the Woman’s World was remarking that “square and heart-shaped bodice openings in front are going out of date and the choice lies between a smart tea-gown and full dress”.

- 1875 – Swoon!

- 1876 pink ball gown, lace and green sash trained gown

- 1875 English ball gowns

- 1876 French ballgowns

Ball dresses were low at the back and at the front; they were cut round or slightly square in the late 1870s and early 1880s, but by the mid- 1880s they often had a deep V-shaped line or a heart-shaped curve in front. Sleeves were almost non-existent in full evening dress for most of the period, but they were beginning to reappear by 1890.

Sleeves of day dresses were generally long and fitting, with a trimmed cuff, which became less conspicuous by 1880; narrow sleeves with plain cuffs were general for most of the 1880s. These were long to the wrist until 1883, and then were often shorter, ending between the wrist and the elbow.

By 1889, sleeves were beginning to rise above the shoulder in a small puff, a detail characteristic of the early 1890s until 1893. Sleeves ending at the elbow with a frilled trimming, and slashed sleeves showing a different colour beneath, were worn in the late 1870s.

- 1882 Mme Pelletier-Vidal evening gown with V neckline

- 1887 Mme Pelletier-Vidal evening gown with square neckline

- 1888 Worth evening gown with heart neckline

Up to 1885, evening dresses could hardly show more trimming than day dresses, and differed only in decolletage and fabric. In the late 1880s, the style for many of the evening dresses, particularly those made of the heavier fabrics, was a long tunic open at the front to reveal the front panel of the skirt. This was often very richly ornamented, particularly in the elaborate bead embroidery fashionable at this time.

The waistcoat or plastron was in a different material in the same color as the bodice, in a different colour of the same material, or different in both color and fabric. Lace was also much used in this position in the mid-188os.

- 1883 lace trimmed dinner gown

- 1883 lace trimmed ball gown (R)

This type of trimming was sometimes applied to evening bodices, which in the late 1880s sometimes had a front fastening as well as a back fastening. “The stomacher style of trimming gives an easy pretext for hiding the front fastening and allowing the lacing at the back only to be visible” (Lady’s World, 1887).

By the end of the 1880s, the bodice was becoming the more important part of the dress: “It matters little how plain the skirt is; the bodice is all-important; and for dressy occasions, full vests and jabots are almost a necessity” (Woman’s World, 1889).

For evening wear, there was the combination of plain silk or velvet with figured or embroidered silk. In the late 1880s, when very rich figured materials such as velvet-figured silks were very fashionable, they were usually combined with a plain silk or satin.

Learn how to DIY a Victorian ballgown. Or shop for ballgowns and evening dresses.

1887 Velvet and lace evening dress

Fabrics and Colors

All through the period there was a fashion for using more than one material in a dress. Day dresses of the late 1870s might be made of two different materials of one shade of color, for example, poplin and velvet; or a check silk might be used with a satin of the same shade as the dominant colour of the check.

1883 check silks

Woollen fabrics had a new importance as fashionable fabrics during this period. They were used in two different ways. The sheath-like dresses of the late 1870s demanded fabrics which would fit closely and drape softly on the figure.

For this the softer, lighter woollen materials were used, and these are often found, combined with silk, even in evening dresses ; twilled cashmere was used chiefly in the 1870s, and the lighter woollen muslins, nun’s veiling and mousseline de laine in the 1880s.

Serge, flannel and light printed woollen fabrics were used for informal outdoor dress. The other use was of the heavier woollen fabrics, tweeds and habit cloths for the tailor-made dresses and costumes, which were the most important and significant garments in all the fashion changes of the reign. “Our home manufactures we note daily in the hundreds of neat tailor-clad figures that flit along our busy streets” (Ladies’ Gazette of Fashion, 1881).

1881 blue plaid and black dresses

By 1889 these tailor-made gowns with their plain severe outlines had spread from their beginnings as outdoor and travelling garments. The rougher woollen fabrics remained in use for this type of wear, but wool, in the close smooth cloths, was a fashionable material for general wear.

“A tailor-made gown … is suited to almost all occasions when morning dress is permissible. Such costumes are worn in London at the smartest weddings and afternoon parties, and it would not be out of place in a long country walk across stubble fields, or for a tour abroad” (Woman’s World, 1889).

1881 dresses for wlaking

A fabric used for stockings and gloves for many years was given a new fashionable use in 1879 and made a new fashionable garment.

The jersey, a bodice without fastening, or with a back fastening, was made in wool or silk jersey or stockinette. It provided a more sheath-like garment for the upper part of the body than was achieved in any other fabric. It was worn with a serge or flannel skirt or, in summer, a linen or cotton one, and was particularly popular for tennis wear between 1879 and 1882.

1887 skirt and jacket

The need for materials which would drape softly meant a revival of the lighter silks. Surah, a soft twilled silk, was fashionable for most of the period.

Madras or Delhi muslin, “looking . . . more like a transparent brocade than anything else” (Sylvia’s Home Journal, 1880) is often found in dresses of the late 1870s and early 1880s.

1881 fancy dresses

Many washing materials were used in summer woollens. Natural colored canvas, often embroidered in color, was a particularly characteristic fabric for summer dresses in the mid- 1 880s.

Colored cottons with white embroidery and embroidered tussore silk, a wild silk in natural colour, were also fashionable.

1883 sateen printed

Amongst the heavier fabrics, plush, a cotton velvet with a deep pile, was much worn in the early 1880s. Other heavy fabrics of frequent use were brocaded silk; satin figured in cut and uncut velvet ; and matelasse”, a silk figured so that it appears to be quilted.

Small floral patterns, closely woven, were generally used for figured materials in the late 1870s and early 1880s. The patterns tended to become larger towards the end of the 1880s, although the smaller patterns were still used.

1883 printed fabric dresses

The influence of the eighteenth-century patterns can also be seen in both printed and woven fabrics. Sometimes dresses of this period will be found remade from eighteenth-century silk or printed cotton.

Printed silks, woollens and cottons were all fashionable during the 1880s, in stripes, spots and striped patterns.

- 1883 French sateen

- 1883 French sateen

It was generally a period of rich and varied colour, sometimes rather harsh color and garnish combinations, but there are from the 1880s an almost equal number of dresses in very light shades. “The lighter the tint, the more elegant the gown. The skirts of plain colour are worn with bodice and wide-spreading coat tails of flowered material to match” (Queen, 1883).

The lace which was used in profusion to trim the draperies of the dress, and for the collars and plastrons added to them in the early 1880s, was often coffee-coloured. Some of the lighter summer dresses were trimmed with bows and loops of brightly colored ribbon.

1880s fashion colors

Lighter colours were more general for evening than day dress. Blue and white and red or pink and white are often found in the summer washing dresses. Many shades of blue were worn, particularly in the 1880s, and rich browns, chartreuse and olive green; but red, in rich wine and jewel-like shades, was perhaps the dominant color of the whole period.

Claret, garnet, crimson and plum-colour were used as the single colour of a dress, using two materials, velvet and satin; or they were used, particularly in the late 1870s, with a contrasting neutral shade, garnet and grey, claret and cream.

1882 dress colors with ribbon trim

A combination of bright red and dark grey was also popular in the 1 880s.

Shop Victorian sewing patterns.

Outerwear – Coats, Cloaks, Mantels

During the 1880s, mantles in great variety were the general form, and coats and cloaks less characteristic.

During the 1880s, the mantle was the usual form. The long, slim line of the late 1870s continued for the first years of the decade and the longer mantles generally increased their length, so that often only the hem of the dress was visible beneath. The use of the dolman types of sleeve was, in general, all these full- length forms, turning the coat into a full-length mantle, fitting in all but the sleeves.

From 1883, the slimness of the line broke to take the increasing fullness in the skirt of the dress. The fullness of the evening mantles was given either by pleating, falling from the waist at the centre back, or by the width of the cape-like side sections, gored to a narrow back width. There was sometimes a combination of both these devices in full- or three-quarter-length mantles.

1883 dolman sleeve

Short mantles were also worn, in great variety, in the 1880s. Some had fitted backs, ending at the bustle, or were a little longer, opening to go over it. They were usually trimmed at this point with a bow of ribbon.

The back and front sections were usually narrow and the cape shaping for the arms, full. This form with the wide cape from the shoulder continued to be worn on both long and short mantles, but the short sleeve starting from the elbow was perhaps the more general form for the 1880s.

- 1889 wraps or mantel coats

- 1889 wraps or mantel coats

Sleeve shaping which ended at the elbow and revealed the lower half of the arm also appeared in the lighter mantles of this time. From 1885, the sling sleeve, formed by the front section of the mantle being turned up inside to form a sling, was a distinctive fashion. Many of the shorter mantles had their narrow fronts extending into scarf ends.

Short jackets, usually in cloth, were worn as a plainer fashion. Shorter than the fitted jackets of the 1870s, they were made with closely fitting bodice, and basque-shaped with pleating at the back to the closely over the hips.

1883 short, fitted coats

There were short capes of two kinds: one was a decorative addition to the costume, light in fabric, but heavily decorated, usually with beads; the other was a short cloth cape, often a double or triple cape, which appeared in the second half of the decade as a driving cape.

1884 cape and mantel

A large proportion of the mantles and capes of the 1880s were black. The fabrics used for them were velvet and corded silk, and also the lighter fabrics, net or lace, weighted with bead embroidery.

Mantles in bright, rich colours were usually in plush, one of the most characteristic fabrics of the 1880s. The heavier figured silks were also fashionable and appeared in the mantles.

Figured materials other than silk were also used, and there are many examples of a woven shawl of earlier fashion being cut up to make a mantle of the 1880s.

The weight of the heavier winter mantles was often increased by a quilted lining. The mantles bore a great deal of trimming, chenille fringe, silk fringe, edgings of fur and feathers, lace, braid, and beaded braid and embroidery.

1886 boucle coats

From 1884, jackets and mantles of day wear often had a high, fitting band at the neck, like the dresses. At the end of the decade, both the true sleeve of the jackets and the sleeve-shaping of the mantles—which usually included a seam over the shoulder from front to back—rose above the shoulder seam.

Shop Victorian coats, capes and wraps.

1866 fur mantels

1870s-1880s Poor Women

While the above information was about trending ladies fashion for upper and wealthier middle classes, the question remains, what did Victorian women wear who were poor or working class?

Very little working class clothing has survived from the 1870s and 1880s. Once clothing was worn out it was re-made into clothing for children, accessories, household supplies or rags. What we know is based on a few photographs of street scenes and later, factory workers.

1877 baskets used to sell goods at market

Family photographs rarely show what poor women wore on a daily basis. Photography was a luxury. Clothing worn in family portraits were often borrowed or rented from the photographer or a resale clothing shop. You can often see that they fit poorly or were in styles a few years older than the date of the portrait.

Poor women wore only what they could afford to purchase second hand or receive as a gift if they were in service to a wealthier lady. Hand me downs and second-hand clothing were stripped of trim, lace, and buttons. Even the nicest of dresses was plain with only the decorative trim she could repurpose from other clothing.

1876 poor grandmother resting with a baby. She wears no petticoat under her skirt. Her cape in well worn.

The poorest of the poor didn’t have time to sew and trim new-to-them garments. Many couldn’t even afford to replace a missing button (they would need a needle, thread and button- an expense of at least a few dollars.) Most extra trim was saved for hats where it was seen the most.

Clothing that was passed down was at least several years old in style up to 20 years old for something durable like wool. Second-hand shops and street vendors would repair old garments and re-sell them to new owners.

Skirts were simple round shapes, bodices tailored but never perfectly fitting. A bodice from one dress was mixed with the skirt of another. The skirt length was sometimes too short (an advantage for the working classes) or sleeves too long. Skirt hems wore out on the dirty streets and needed frequent replacement with a ruffled hem.

1876 lady in black has her sleeves rolled up. Her dress has a replacement hem

Coats and jackets were the most expensive item and a luxury for many. Women knit or crocheted simple shawls and wraps or recycled old skirts into capes.

Most women wore underwear such as corsets and petticoats. Warm knit stockings were essential in winter.

Victorian Hats, Shoes and Accessories History

Hats- Lear about Victorian hat fashions and shop hats

Shoes- Ladies boots for day and low heel pumps for evenings

Handbags- History of what to carry and how with a handbag

Stockings– Examples, history and pictures below the ads

Gloves- History od ladies day and evening gloves

Parasol- Ladies parasols and umbrella history

Underwear – Shop petticoats, chemise and other lingerie

Hand Fans- These useful fans are a must for an evening of dancing

Victorian Hair Accessories- Hair decorations and wigs for sale online

Makeup and Beauty- History of Victorian makeup and how to create a look for your face

How to Make a 1880s Outfit

Sew an 1880s costumes from one of these 1880s Sewing Patterns.

Learn how to make a 1870s- 1880s costume with little to no sewing skills here.

- 1870s style costume I put together

- Late 1880s style with small bustle

- Black hi-low ruffled skirt acts as the bustle on this dress. Sash belt and brooch. Black lace blouse.

- View of the side with safety pins creating the bustle

You can purchase Victorian-inspired skirts, tops, jackets, belts, shoes, and hats to create an 1870s and 1880s history bounding costume like this:

1870-1880s costume – A bustled striped skirt with a velvet Gothic style top, button boots and small hat

Shop 1880s style dresses, costumes and clothing:

Find even more Victorian clothing here.

Debbie Sessions has been teaching fashion history and helping people dress for vintage themed events since 2009. She has turned a hobby into VintageDancer.com with hundreds of well researched articles and hand picked links to vintage inspired clothing online. She aims to make dressing accurately (or not) an affordable option for all. Oh, and she dances too.